Michael Harper Speaks with Alexandra Teague

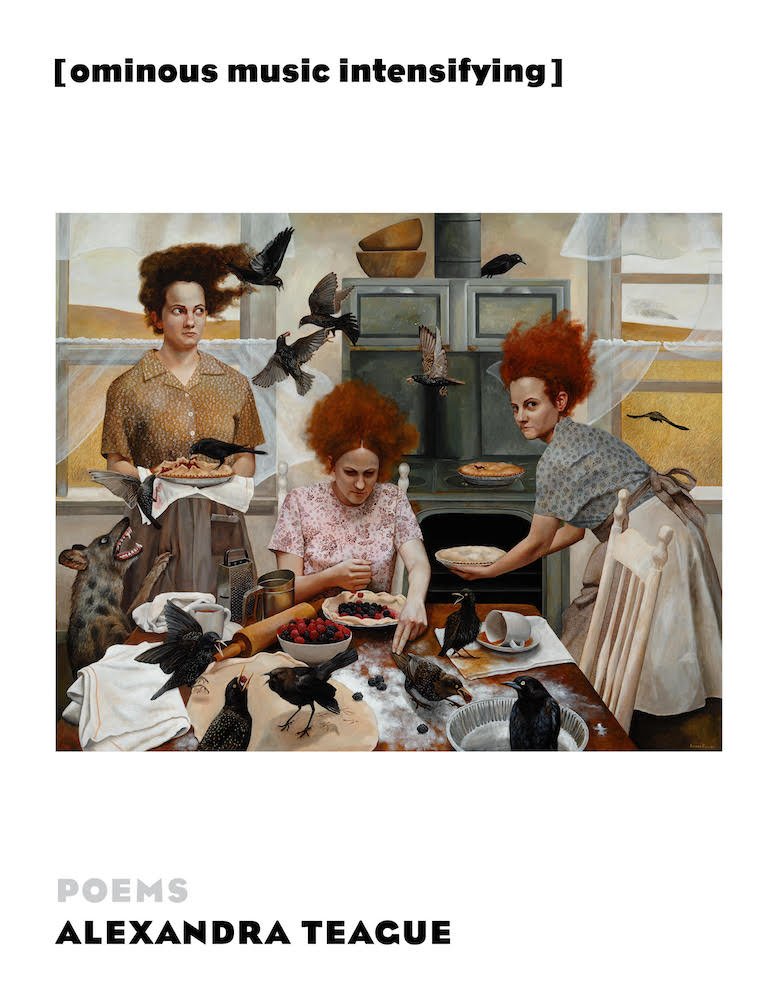

Alexandra Teague is the author of [ominous music intensifying] (Persea 2024), Spinning Tea Cups: A Mythical American Memoir, three prior poetry collections, and a novel, as well as co-editor of Bullets into Bells: Poets & Citizens Respond to Gun Violence. She is a professor at University of Idaho where she co-directs the MFA program.

MH: This is your fourth book of poetry, but you’ve also published a book of fiction and earlier this year your memoir in essays, Spinning Tea Cups, was published by Oregon State Press. What do different genres unlock in your writing and how do you choose what genre a specific project is going to take?

AT: I’m fascinated by form, poetically and otherwise, and I’m always interested in how putting ideas into a particular form creates and affects meaning. I switched to essays for the family stories that became my memoir because I felt as if the sort of associative and sound-driven poetic moves I’d been making when writing about those stories were short-circuiting some wrangling directly with meaning-making and more complex truths that I needed to write toward. Writing essays forced me to slow down and ask different, more overt questions, and figure out what I might believe.

For the subjects in [ominous music intensifying], though, I want more associative moves to be at play, with the layerings and simultaneity that can exist in poetry. I’ve thought for years about Charles Olson’s definition of poetry as a “high-energy construct,” and in “Mean High Water,” which is in a form I invented called the American Gyre, every fragment appears once in the first half, and then after the midpoint, they all remix, swirling together the energy of the original phrases in new ways (with the rule that no two phrases that were adjacent originally can be again). I’ve been interested for years in repetitive forms like pantoums and sestinas, and this poem is an outgrowth of that, but with a more manic, insistent energy. Gertrude Stein famously said there is no repetition, only insistence, and I got fascinated with that idea, partly through the wonderful Irish poet Ailbhe Darcy’s book Insistence, which was a finalist for the T.S. Eliot Prize the year I was living in Wales, and which is itself in conversation with Inger Christensen’s alphabet.

In a time when it feels like people on different social media platforms and news stations are literally talking over one another about separate realities, and when it felt as if my own experience of the world kept getting radically remixed—my first time living overseas for a year, certainly the first pandemic lockdown I’d lived through—questions of how to use poetry to keep reapproaching emotions and experiences and ideas from new, insistent angles became particularly urgent and interesting for me.

MH: How do you think of sound while writing and how does that change depending on the genre or project you are working on?

AT: I’ve always written centrally by ear—i.e. by hearing when a word or line or poem is right—and while I don’t frequently write in meter, I definitely often work against a sort of ruffled and highly-enjambed iambic base, and am also paying a lot of attention to sonic echoes, whether direct rhymes or other patterns of recurring sounds that are driving the poem forward. I love being led by sound, and in a line like “something / squawky to it, something donkey about the wheels,” the word “donkey” emerged originally as a play off the sound of “squawky,” and then I decided to leave it because it’s strange and gets at another aspect of the poem’s fiddle music. I love that rhymes are simultaneously comfortably familiar and a way to “open the poem to wildness” as Tony Barnstone wonderfully puts it. Because the moves in poetry can be faster and more elliptical than prose—i.e. sound can be what drives the leaps with less need to explain or maintain narrative—I let sound drive more overtly when I’m drafting poems. But I very much hone my prose sentences by sound, and am definitely led in drafting fiction and nonfiction by the sounds and a sense of voice as well.

Most of these poems are longer. I believe only two are under a page. As they lengthen, they tend to pick up a sort of tumbling momentum and curve in unexpected ways like a river running downhill. How do you see space working in your work and what does it allow your poems and thinking to do? I guess I’m just asking, why do you hate short poems so much?

I’m in awe of great short poems, and I’ve never yet known how to write them. My shortest poem ever must be something like ten lines, whereas a poem like Les Murray’s “Drought Dust on the Crockery” does all its strange, deceptively simple, perfect work in five lines: “Things were not better / when I was young: / things were poorer and harsher, / drought dust on the crockery, / and I was young.” Maybe someday I’ll be old or smart enough to write a poem like that or Jane Hirschfield’s eight-line “Late Self-Portrait of Rembrandt,” which I was just looking at with my students, and which has so much fascinating space in its moves from stanza to stanza.

I’d love to write a poem that holds those kinds of silences and spaces while still feeling pressurized and layered, but I’m also a maximalist who tends to tell stories and think about experience in a this-connects-to-this-and-also-this-and-also. . . way, and after writing poems with a lot of long syntax driving them in my last collection, I felt compelled to push that impulse to the brink—and literally over Niagara Falls—in this collection. That felt like the right way to get at the swirl of violence and beauty and confusion and crisscrossed communication (within my own body and within this country) for this collection’s subjects. But this book feels like it might be a turning point toward more space or silence, and my next project is to study translation and work on some Spanish translations, which will slow me down and I hope teach me how poems can move in entirely different ways.

MH: Was there any writing or art that acted as inspiration or a guiding star for this collection?

AT: There wasn’t one guiding star, but I open the collection with “America the Beautiful: Thrifstore” because the thriftstore aesthetic of bringing together cast-off, maybe broken, maybe amazing parts of this country and my own experiences felt so central to what the collection ends up doing. This is definitely my thingiest collection, and the poems cite so many books and movies and people and objects of the world.

Another central metaphor/inspiration were the 19th-century “crossed letters” I saw in Trinity College in Dublin when I was on sabbatical, which are written horizontally across the page and then vertically over that, and which I started thinking of in relation to my desire to create a layered experience of this country that’s so often at odds with itself.

Charles Olson’s poetry kept surfacing, and I was obsessed with David Bowie’s “Ashes to Ashes” video with him in a Poirot suit, with these surreal beach scenes and washed-out colors. That makes a cameo. During the pandemic, I kept thinking about two lines that made it into “Mean High Water”: Martin Gore’s “Charm’s in limited supply and refusing to stretch” and the poet Eunice Odio’s “There’s no wind in this part of your voyage. I repeat: we are gyrating motionless.” And at one point I played Marilyn Manson’s “We’re From America” over and over as I tried to work through one of the Rough Beast poems (I don’t usually listen to Marilyn Manson, or to music as I write, but that song felt relevant). The movie The Witch led to the book’s title. Jimi Hendrix’s tearing apart of “The Star Spangled Banner” is definitely here, with its pushing of one of the iconic songs of this country to near unrecognizability. I’m definitely not comparing myself to Hendrix’s Woodstock performance, but I think the impulse of this collection is akin to the way his “Woodstock anthem was both an expression of protest at the obscene violence of a wholly unnecessary war and an affirmation of aspects of the American experiment entirely worth fighting for,” as Paul Grimstad described it in The New Yorker.

MH: I’m cautious to call something political because it is often conflated with didactic, but this collection is overtly political. There is even an open letter to Mitch McConnell. Do you think art is inherently political and some work is just more open about it? And how does it feel to be creating a piece of art like this that is being released so close to the election?

AT: I think all art is political—whether through accepting the status quo or imagining alternatives, and whether through giving “name to the nameless” (as Audre Lorde writes in “Poetry is Not a Luxury”) or overtly addressing political subjects. Of course that all exists on a spectrum. And for years I was so scared of writing didactically that I didn’t overtly address the political subjects I feel most strongly about. Over the years, I’ve read so much smart, highly charged, and not-didactic poetry that allows complexities to co-exist (Evie Shockley, Tyehimba Jess, and Mark Doty, and further back, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Audre Lorde and June Jordan and so many others, including the poets in Bullets into Bells: Poets & Citizens Respond to Gun Violence, which I had the honor of co-editing with Dean Rader and Brian Clements in 2017). I hope I’ve found my own techniques for being more directly political while also including complexity and uncertainty and the ways in which I’m implicated in systems I might not agree with, and the ways in which it’s all so much bigger than can ever be contained in a poem.

The maximalist aesthetic of these poems is definitely counter to the often sound-bite, hot-take culture we live in. One of the things I love about poems is that even though they move fast in some ways, they’re also often not linear in their energy and can slow us down and get us to read ideas and emotions and images and sounds back onto one another to consider more complex resonances. Poems can also move us past our own initial more simplistic reactions as a reader or writer. I wrote the series of Mitch McConnell sonnets at a point that I was so angry with him and what he was doing to this country that I needed to channel the rage somewhere. I didn’t think I had anything smart to say except “stop destroying everything!!!!!” The poem allowed me to rage, but also led me toward far more interesting conversations about what I truly value about this country, who I am, and have been, as a person in it, what I think about aliens and Ibiza foam parties. . . You know, the things one writes about to Mitch McConnell. I never anticipated that the book would come out exactly a month before the election in such a charged year, and I’ve thought for more than a decade that some of my recurring subjects—like gun violence—might be substantially altered by legislation and made less relevant. For better or worse, these poems still feel very relevant to me.

MH: This collection is constantly pushing at the borders of the concept of America but in doing so is forced to acknowledge these entrenched symbols and ideas of American society that can’t be avoided, like our history of violence. There seems to be a conscious effort to carry an awareness of this complicated and often shameful past forward into the future, and not only bring it with but incorporate it into identity in a complicated way. How do you articulate an identity that is so undefinable and in conflict with itself? Why is poetry a unique form in which to express this complexity?

AT: The poet and feminist theorist Adrienne Rich defined truth as an “increasingly complexity” and even if she didn’t fully live up to her own definition in her politics, I love this definition so much. I want to use forms (whether the unexpected bringing together of a traditional patriotic song with a contemporary place or event, or the remixing in the American Gyre) to get at that increasing complexity and not shy away from the parts that might feel inconsistent or confusing. Of course poetry has a long tradition—going back to Keats’ idea of “negative capability” and before—of allowing mystery and unknowing, and I’m really interested by the ways that bringing together voices or images or ideas that don’t usually coexist can also work to defamiliarize them.

Sometimes I think our symbols in this country and our identity feel too boiled down (at least in portions of the political spectrum). We all know what America’s patriotic songs sound like, but what happens if their lyrics are brought into conversation with other traditions and images that don’t belong—but maybe also do: that allow us to see the ways in which the stories we culturally tell ourselves, and the ways the past is carried forward, are in really complex conversation with the present. This all sounds really serious, but one of the ways that poetry can also offer a different vantage point is by bringing in absurdist humor, which I do throughout, like considering what it means if everything is “a sad clown painting” or having Yeats’ Rough Beast using his claws in a painting class where one of the colors is “Trump.”

MH: The title, [ominous music intensifying], expresses the sense of dread that is lurking in the shadows of many of these poems. Whether it is gun violence or environmental devastation, dread pops its head up constantly. Can you talk about dread in this work, and what it’s like to have this tension hovering in the background?

AT: I go to poetry in part to do something constructive and more complicated and I hope meaningful—and sometimes, as I just said, also funny—with the looming dread that I often feel about the directions this country is going. There’s only so much rage and letter-writing-to-senators one can do about mass shooting after mass shooting, for instance. I mean, I don’t stop with direct actions or voting, of course, but at some point, messing around with words and seeing where the music of the line takes me, and seeing what images surprise me, is a way of re-seeing the same frustrations and hopefully bringing some more layered meaning to them. A way out of some of the tension and exhaustion.

MH: Yeats' apocalyptic Rough Beast goes on quite a journey through this collection. At different points it can be found in outer space and taking a painting class. Can you discuss your use of the Rough Beast in this collection and the journey it goes on?

AT: Oh yes! I’m so glad to talk about the Rough Beast. After I started writing these poems, I read somewhere that Yeats’ “The Second Coming” is one of the top two most quoted poems in the English language, so I’m certainly not alone in loving it or being haunted by its images and famous phrases, but bizarrely, I’ve never seen anyone really imagining what or who the Rough Beast is beyond a figure of the apocalypse who’s “slouching toward Bethlehem” at the poem’s end. I needed to write an environmental poem for a reading in maybe 2017, and for whatever reason, I started writing about the Rough Beast being in the grocery store looking at rows of bottled water. That poem didn’t really work, but the figure stayed with me. From the start, I imagined him as a sympathetic, misunderstood, confused figure, who is not meaning to be the symbol of the apocalypse (or the many apocalypses) but that is having all this literary and cultural baggage put on him.

In my last book, Or What We’ll Call Desire (Persea 2019), the Russian fairytale witch Baba Yaga sometimes speaks about contemporary situations, in a way that’s definitely a precursor, but I’m less interested in the Rough Beast’s voice, and more in how he’d be seen, or experience, different contemporary environments and situations. Midway through writing these poems, I read one at the Port Townsend Writers’ Conference, where Bruce Beasley was also teaching, and Bruce wonderfully shared with me that in an early draft of “The Second Coming,” Yeats had capitalized Rough Beast, which felt like historical validation of my take on him as a specific character. My friend the poet Laura Read has started calling my—and now her—tendency to write about historical or literary figures, our “historical friends.” And I definitely feel like the Rough Beast and I befriended each other over these years.

MH: I’m quite amazed by how cohesive the narrative arc of this collection is. All these poems feel not only like they belong to one piece of writing, but there is a smoothness to how they fit together to tell a larger story. Can you discuss how this collection came together and at what point you started seeing the outline of the finished version of the book?

AT: I’m so glad that you see it as so cohesive. The first part that began to come into focus—just after finishing my last collection, Or What We’ll Call Desire—were a series of poems that recontextualize American patriotic songs in relation to contemporary events. A bit later, the Rough Beast walked into a poem and those became two emerging threads I thought the collection would gravitate around even more. But then I went on sabbatical to Cardiff, Wales, for a year, and in the midst of a lot of grief and anger about American politics (ongoing mass shootings, the Trump presidency, and the Kavanagh hearings to name three), I got a radically different perspective on my own country, and what it felt like to live for awhile in a society without the U.S. level of fear or anger. Tonally different, more personal poems started emerging, as well as poems like “‘My Country, ‘Tis of Thee’ (arranged for Brazen Bull)” that were influenced by the more rhyme and stress-heavy poetry I was hearing from Welsh and other U.K. poets, as well as by being tangentially immersed in the music program at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama, where my husband was studying.

I came home in Fall of 2019, and then the pandemic struck, and everything radically changed again, and during a time of profound depression and isolation, in which I had a very hard time writing, what became the core of the collection eventually emerged, including “Crossed Letters from a Concerned American” and “Field Blocks.” So the process of writing honestly felt anything but cohesive, and as if I kept reimagining what this country was and who I might be in it. But my thinking about music and the Rough Beast carried through those years with me (the Rough Beast has to confront the pandemic in his spacesuit too), and the book really came together once I finished—finally—“Mean High Water,” which I spent much of the pandemic swirling through various failed drafts of, and which feels like the crescendo to preoccupations with remixing and simultaneously trying to reckon with all this too-muchness and passage of time and experience and violence and beauty.

MH: The book is ominous, hence the title, but the ending left me feeling almost hopeful, as if I was momentarily released from a burden I didn’t know I was carrying. There is possibility at the end that is cosmic in scope, but also personal. I guess my question is, how is consciousness expanded in a world with such powerful myths and symbols and ideals? And where should we be looking for them?

AT: Oh wow. Thank you for saying that you felt that way. I’ve certainly had other poets and readers over the years say that my poetry tends really dark, but I strongly believe that confronting dystopian thinking and facing terrible social realities is part of a forward-thinking, even utopian impulse to reimagine what society can be. I’ve already quoted Audre Lorde’s “Poetry is Not a Luxury,” but I absolutely love and believe her arguments, which open, “The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has the direct bearing on the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives.” She sees poetry as part of the “illumination,” the “quality of light” that allows us to see differently, and articulate alternatives. I’m an idealist, and I think we can do so so much better than we are right now as a country, and I want, in my small poetic way, to help add to the depth and complexity and also humanity of the conversations about our history and present, while also reckoning with my own idiosyncratic experiences as someone from—at least on one side—a poor fairly rural family, and someone who got married very young, and now that I’m about to turn fifty is thinking about my own history and priorities in a female body, with particular traumas and definitely also privileges. I write because I go to writing—and other forms of art, including visual art and music and movies—to try to understand more fully what it is to be human and part of a society, and what other people’s perspectives and experiences look and feel like. So I guess I’d say that we should be looking for ideals partly in art, which is probably a good thing for me to believe as a writer and writing professor!

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

© 2024 Iron Oak Editions

Stay Connected to Our Literary Community. Subscribe to Our Newsletter

October 1, 2024

Michael Harper teaches at Northern New Mexico College. His most recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in Ninth Letter, X-R-A-Y, Hobart, Fugue, Terrain.org, The Los Angeles Review, and others.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Listen to Teague read "America The Beautiful Thrift Store"

Listen to Teague read "My Country Tis of Thee Arranged for Brazen Bull"