Lissa Batista

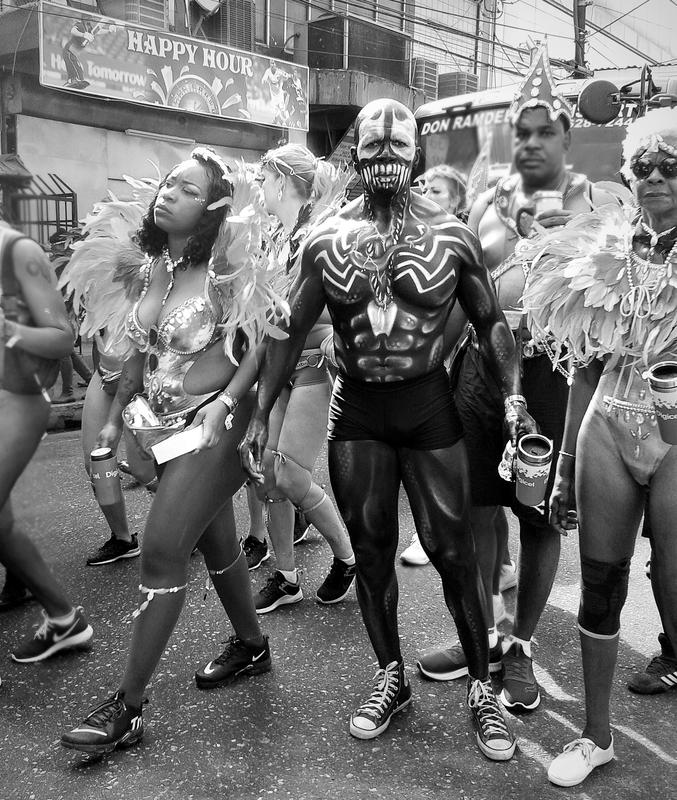

Photo by Jhaye-Q Shows from Pexels

LIssa Batista is a Brazilian-born poet raised in Miami, Florida where she is an MFA candidate at Florida International University. She lives with her hairless cat and her son, teaching language arts to middle schoolers. Her favorite drink is an espresso martini, and she can karaoke her heart out. Her works can be found or forthcoming with Bellingham Review, SoFloPoJo, Lucky Jefferson, Tofu Ink, Cathexis Northwest Press, and others.

Dreaming in Brazil

In Brazil, during springtime, we wake up in samba clothes. We wear pink chicken feathers tucked in metal caged bras, emu feathers for the headpiece. Beads fringe the lining of our underwear, our hips bouncing to the beat of brewing coffee on the stove.

In Brazil, the cops are robbers. The robbers are rich. The rich are natives in the amazon forests, dancing for rain. The rain, a guide to God.

In Brazil, the morning coffee makes itself.

There was a padaria on the corner from grandma’s house, Babaloos of every color next to boxes of Prestigio chocolates under the counter where they sold Sonhos, donuts cut in half and filled with Doce de Leite. I’d have enough coins to buy a Pitchula soda, and wait outside for the churrasqueiro to grill skewered, chicken hearts in the afternoon. I ate chicken hearts like green grapes— popping one by one, squirting its juice on the sidewalk through my gapped-tooth smile.

When I eat chicken hearts, I think I’m the Evil Queen eating my heart out.

In Brazil, we kill backyard dogs with rat poison tucked inside a raw beef meatball. We roll it under iron gates or toss it over the 8-foot brick wall our grandfathers built.

In Brazil, everyone owns a two-gun minimum. To have the right to own a gun, we kill one family member.

In Brazil, to dream of a coiled snake means someone is gossiping about you.

I dreamt of my hands covered with coils of baby snakes as I watched a burning helicopter crash into a bay, the snakes falling from my hands into the water. The next morning, my cousin shot and killed a man for spreading rumors about them cheating on their wife.

In Brazil, the sun is a red ball.

My great-grandmother poisoned her husband with rat-killing chemicals in his galinhada at lunchtime. My aunt, a teenager, dropped her infant sister from a hammock on the porch. My cousin shot a man they thought was their father.

In Brazil, my mother was a Beauty Pageant Queen. To get there, she had to kill a cow— make a hatchet, use the blunt side, strike the cow between the eyes. The cow kneels down, then lies on its side.

Go to Rio’s Carnival for giant floats the size of small buildings, choreographed dancing, of the samba that wears on anyone’s feet: from the stiletto Pradas to Havaianas to feet bared in red mud, feet rainbows on Copacabana.

In Brazil, women get away with murder.

Slit the neck, like knifing peanut butter out of the jar, drain the blood for twenty minutes. On the side facing us, skin her while she still bleeds the Brazilian Flag.

My cousin never gets caught. After 48 hours, the police stop the pursuit.

To dance samba, the women wobble their hips on the balls of their feet. They tiptoe in half moon patterns; step up then bring it back with a wave. Repeat on the other side. The two half moons, a rainbow.

The men dance samba on the balls of their feet.

After my mother killed the cow, she had to battle her father in the front yard, everyone watching. She was not allowed weapons, but she cheated and kept a knife in her back pocket.

In Brazil, we are the villain and the victim.

Hang the cow. Remove the skin from the other side with the sharpest knife you have. Remove the legs by cutting into the knee joints. Chop off the head. Save the hooves. Make Mocoto.

In Brazil, the slaves won independency with a meia-lua kick to the colonizer’s face. That’s why Capoeira is Brazil’s favorite song.

In Brazil, we pray to the half-moon.

In Brazil, there are no sweet peppers.

In Brazil, the cow head is put to dry, to become the scarecrow on the cornfields, sugarcane fields, coffee fields, sunflower fields, empty fields, because Brazilians buy land but can’t grow.

When I knew my parents weren’t going to last, we were passing car-sized termite hills on the side of the roads. Ten years before this moment, I tried to knock them down. I kicked at it, mounds as tall as my eight-year-old body, made of clay. I imagined inside a complicated maze with cozy, cramped homes. Giant mounds, but they were in it together. I wondered how long I could keep my parents together in the shell of our car passing sunflower fields and termite hills.

Open the stomach, remove the organs— the heart, the stomach, liver, kidneys. In Brazil, we eat those, too. From tail to neck, separate the body with a knife, half and half, left rib and right rib. A butterfly.

In Brazil, we will eat everything.

Go to Carnival in any other city, and the locals have their TV on Globo. Watch samba schools from a distance. Go to their open windows. They will give you wine in plastic cups, a plate of galinhada. The people at the bar will eat with you. Late-night grandmothers will walk you home. You wake up to coffee brewing, to rainbows of people outside your door. To more food. To more wine.

In Brazil, the stars are bigger than the moon. The night sky is the movie theater.

My aunt ground glass with pestle and mortar, the same way Brazilians do with garlic and salt, for seasoning. She sprinkled the glass like sugar over the rice pudding, his favorite. She added cinnamon powder over it to stop the glass from glistening. He took a bite. He knew. He ate the whole bowl.

In Brazil, we don’t drive at night. Once, my father hit a horse when I was a baby in the front seat with my mother.

In Brazil, when the cow is being killed, they kneel to pray to God for our forgiveness.

My mother says she dreamt of horses the day she stabbed her father in the eye.

The year my parents separated, my dad went to Carnival for the last time. While he was there, I slept in the bed with my mother, and we both dreamt that we were underwater, dredging slowly through the sand, the water so clear we could see an octopus walking, snakes sleeping in coils. Ink comes from above and blankets us like a thick carpet. An unbreathable darkness.

Carnival is making pão de queijo, adding an extra tablespoon of cane sugar to your coffee. Carnival is a house party that sambas out into the neighboring streets. Carnival é pagode, axé, forró, sertanejo, batucadas. Carnival is family. Carnival is pamonhas wrapped in corn husks. Carnival is wearing penas de pavão, or fringed bikinis bedazzled in lantejoulas preto with peacock-feather headdresses.

In Brazil, when we die, we go to Carnival.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

©2022 West Trade Review

Stay Connected to Our Literary Community. Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Listen: