by Mary Sutton

July 16, 2021

Mary Sutton is an NYC-based freelance writer and poetry editor at West Trade Review. She was formerly the NEH Scholar in Public Humanities at Library of America where she worked with Kevin Young on African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle and Song and the book’s companion website www.africanamericanpoetry.org.

The Collection Plate by Kendra Allen; Ecco; 96 pages; $26.99

This is our blooming time, and the collection plate, which serves as a metonym for this début poetry collection about Black families and communal rituals, is indicative of where Black people come together—in church, on the streets in protest, in entrepreneurial camaraderie, and through a shared culture, pieced together from pain and an indomitable will to survive. The beautiful ebony-skinned figure on the cover, not quite one gender or another, emerges in red against a black background, wearing the “Formation” hat of Beyoncé and countless church mothers. Allen’s visual allusions, through both that wardrobe and its color scheme, will be palpable to anyone as attuned as she is to popular culture, history, and our Western literary heritage. It is the “red and black” of Stendhal’s novel of the same name that satirized the restoration of an avaricious ancien régime, only recently outdone in gaudiness by the Trump administration; the red and black of Michelle Obama’s 2008 post-election dress, signaling both the hopes of easing out of an economic depression and into a new nation in which Black progress and prosperity would not only be championed, but normalized.

As with her memoir, When You Learn the Alphabet, which Kiese Laymon selected for the 2018 Iowa Prize for Literary Nonfiction, Allen returns to the subject of the Black family and uses it as the centripetal force from which she explores broader social themes, such as environmental racism and police brutality. Her verse is strongest, however, not when she is narrating the laundry list of injustices confronting Black communities, as in “Naked & Afraid” and “Afraid & Naked,” but when she connects mundane memories to broader, subtler lessons about the vicissitudes of life and personhood, as she does in “The Water Cycle.”

As with her memoir, When You Learn the Alphabet, which Kiese Laymon selected for the 2018 Iowa Prize for Literary Nonfiction, Allen returns to the subject of the Black family and uses it as the centripetal force from which she explores broader social themes, such as environmental racism and police brutality. Her verse is strongest, however, not when she is narrating the laundry list of injustices confronting Black communities, as in “Naked & Afraid” and “Afraid & Naked,” but when she connects mundane memories to broader, subtler lessons about the vicissitudes of life and personhood, as she does in “The Water Cycle.”

Water is a recurring motif in the collection. She invokes it literally to describe how people in predominately Black communities are deprived of clean drinking water. Symbolically, she depicts the ways in which sexism has rendered a Black woman’s body fluid—a place of passage and, too often, a mere receptacle for men’s pleasure, but not one’s own. The collection hinges on five poems entitled “Our Father’s House,” which appear sporadically throughout the book, enumerated with Roman numbers. These taut poems are reminders of how Western patriarchy interferes with Black love. Black women want to love and protect Black men, Allen notes, even when those men don’t love and protect them in return. In “I Hate When Niggas Die” Allen conjures Sojourner Truth and laments how Black women and girls suddenly become beautiful and worthy of comfort only when they lose the Black men closest to them. And this loss, as she reminds us in #FreeMyNiggas, is both endemic and the only birthright for anyone born Black in the United States: “The way we cultivate an offense before we get to fractions […]”

Water is a recurring motif in the collection. She invokes it literally to describe how people in predominately Black communities are deprived of clean drinking water. Symbolically, she depicts the ways in which sexism has rendered a Black woman’s body fluid—a place of passage and, too often, a mere receptacle for men’s pleasure, but not one’s own. The collection hinges on five poems entitled “Our Father’s House,” which appear sporadically throughout the book, enumerated with Roman numbers. These taut poems are reminders of how Western patriarchy interferes with Black love. Black women want to love and protect Black men, Allen notes, even when those men don’t love and protect them in return. In “I Hate When Niggas Die” Allen conjures Sojourner Truth and laments how Black women and girls suddenly become beautiful and worthy of comfort only when they lose the Black men closest to them. And this loss, as she reminds us in #FreeMyNiggas, is both endemic and the only birthright for anyone born Black in the United States: “The way we cultivate an offense before we get to fractions […]”

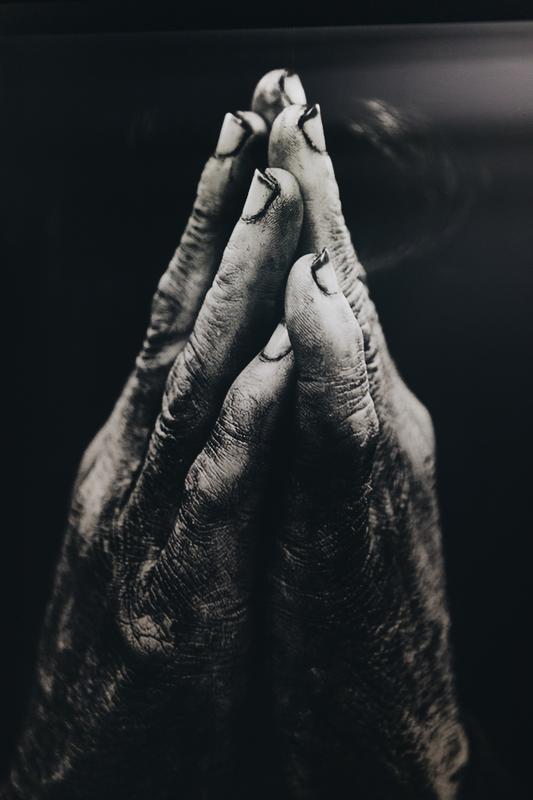

Black communities are not merely connected through shared trauma, but also through shared rituals. What happens, though, when the rituals are inextricable from the trauma? In “Evening Service,” “dead water bugs” float atop baptismal waters—the pool in which the speaker is to be reborn or, really, must forget and “say sorry for wasting [her] first eight years of life.” Allen recognizes the ways in which the Baptist faith of her Dallas upbringing forces an apology out of the convert simply for living, for having a history. She sees, too, the non-consensual aspect of baptism, of feeling compelled to become something befitting the Father, the “modeled men,” and “the pastor [who] is our uncle.” In this ritual, they all “[divest] me of my volition.”

Black communities are not merely connected through shared trauma, but also through shared rituals. What happens, though, when the rituals are inextricable from the trauma? In “Evening Service,” “dead water bugs” float atop baptismal waters—the pool in which the speaker is to be reborn or, really, must forget and “say sorry for wasting [her] first eight years of life.” Allen recognizes the ways in which the Baptist faith of her Dallas upbringing forces an apology out of the convert simply for living, for having a history. She sees, too, the non-consensual aspect of baptism, of feeling compelled to become something befitting the Father, the “modeled men,” and “the pastor [who] is our uncle.” In this ritual, they all “[divest] me of my volition.”

In resistance to this erasure of self, Allen follows “Evening Service” with “Look at the Material,” an unflinching nod at all the stuff that makes up the body and the self. The speaker asserts her completion as a human being, requiring no need for rebirth. Allen knows, too, that Christianity and its key ritual of baptism is linked to the United States’ history of colonialism, genocide, and slavery. Attempts to efface the heritages of indigenous tribes through forced assimilation, particularly conversions to Christianity, were all in the interest of perpetuating the delusion of having discovered a “new world,” one in which the past need not matter. This is, after all, how white people became white. Black people, however, cannot afford to have such loose connections to history. Strength lies in reconnecting with the ancestors, particularly grandmothers, as in “Happy 100th Birthday,” in which Allen’s speaker seeks to “acknowledge [the] fabric” that connects with hers, from inevitable run-ins with the police (“the days the laws came / to pick me / up from the steps”) and soul food dinners (“the Sweet Georgia / Brown plates packed / with mac, cabbage, / & other smothered things”).

In resistance to this erasure of self, Allen follows “Evening Service” with “Look at the Material,” an unflinching nod at all the stuff that makes up the body and the self. The speaker asserts her completion as a human being, requiring no need for rebirth. Allen knows, too, that Christianity and its key ritual of baptism is linked to the United States’ history of colonialism, genocide, and slavery. Attempts to efface the heritages of indigenous tribes through forced assimilation, particularly conversions to Christianity, were all in the interest of perpetuating the delusion of having discovered a “new world,” one in which the past need not matter. This is, after all, how white people became white. Black people, however, cannot afford to have such loose connections to history. Strength lies in reconnecting with the ancestors, particularly grandmothers, as in “Happy 100th Birthday,” in which Allen’s speaker seeks to “acknowledge [the] fabric” that connects with hers, from inevitable run-ins with the police (“the days the laws came / to pick me / up from the steps”) and soul food dinners (“the Sweet Georgia / Brown plates packed / with mac, cabbage, / & other smothered things”).

Throughout the volume, there is tension between connection and rupture. In “I’m the Note Held Towards the End,” the title is also the first line of Allen’s poem, which references Minnie Riperton’s 1975 song “Inside My Love.” Like Riperton, Allen depicts a communion, but hers is an unsettling one. As in other poems in this collection, memories blend and ripple, like waves along the surface of water, eluding our grasp of what is happening and when.

Throughout the volume, there is tension between connection and rupture. In “I’m the Note Held Towards the End,” the title is also the first line of Allen’s poem, which references Minnie Riperton’s 1975 song “Inside My Love.” Like Riperton, Allen depicts a communion, but hers is an unsettling one. As in other poems in this collection, memories blend and ripple, like waves along the surface of water, eluding our grasp of what is happening and when.  Disconnection, particularly that which women often feel from their own bodies, is another recurring motif in the book. Feminism, for Black women, anyway, does not always provide a safe place for exploring personal ruptures. Allen uses quotes from Nannie Helen Burroughs and Carrie Bradshaw, respectively. The first provides the epigraph to “Most Cavalries Have Dead People,” while the latter provides the title to “Nobody Told Her About the End of Love.” Burroughs was an educator and activist who refused to be overcome by sexism and colorism, while Sarah Jessica Parker’s iconic character is an emblem of a capitalist-oriented white feminism defined by the kind of obliviousness that only upper-class white women can afford to have. The latter poem, which reads almost like a tanka, refuses the need to be fixed or addressed by Bradshaw types. But, Allen also admits to her vulnerability, thereby undermining the myth of the Black Superwoman: “when you let someone be / -sides you, / let someone else mend / you, what does that say About / your weakness.” Allen doesn’t punctuate her question. It is as though she wants to focus the reader on the void that she’s interrogating.

Disconnection, particularly that which women often feel from their own bodies, is another recurring motif in the book. Feminism, for Black women, anyway, does not always provide a safe place for exploring personal ruptures. Allen uses quotes from Nannie Helen Burroughs and Carrie Bradshaw, respectively. The first provides the epigraph to “Most Cavalries Have Dead People,” while the latter provides the title to “Nobody Told Her About the End of Love.” Burroughs was an educator and activist who refused to be overcome by sexism and colorism, while Sarah Jessica Parker’s iconic character is an emblem of a capitalist-oriented white feminism defined by the kind of obliviousness that only upper-class white women can afford to have. The latter poem, which reads almost like a tanka, refuses the need to be fixed or addressed by Bradshaw types. But, Allen also admits to her vulnerability, thereby undermining the myth of the Black Superwoman: “when you let someone be / -sides you, / let someone else mend / you, what does that say About / your weakness.” Allen doesn’t punctuate her question. It is as though she wants to focus the reader on the void that she’s interrogating.

Allen often uses language and punctuation to concretize feelings of disconnection. She dissects possessives, suffixes, and contractions from their roots. This helps the reader focus on language as pure sound—morsels of meaning. The “s” that’s left dangling from a possessive takes on the sound of a hiss, while the “n’t” from a contraction mimics the sound of sucking teeth—complete onomatopoeic statements in African American vernacular.

Allen often uses language and punctuation to concretize feelings of disconnection. She dissects possessives, suffixes, and contractions from their roots. This helps the reader focus on language as pure sound—morsels of meaning. The “s” that’s left dangling from a possessive takes on the sound of a hiss, while the “n’t” from a contraction mimics the sound of sucking teeth—complete onomatopoeic statements in African American vernacular.

In some places, however, Allen’s experiments with language don’t achieve what they set out to do, as in “Gifting Back Bread & Barren Land.” Here, Allen becomes distracted by her dexterity—and she really is clever with her odd juxtapositions and alliterative beats. The price of this showing off is that she loses her connection to the reader in these instances, which is critical in a collection that centralizes Black communal rituals.

In some places, however, Allen’s experiments with language don’t achieve what they set out to do, as in “Gifting Back Bread & Barren Land.” Here, Allen becomes distracted by her dexterity—and she really is clever with her odd juxtapositions and alliterative beats. The price of this showing off is that she loses her connection to the reader in these instances, which is critical in a collection that centralizes Black communal rituals.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Taking a Seat at the Table: Kendra Allen débuts her first book of poetry, The Collection Plate