by D.W. White

October 14, 2021

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A Loose Collection of Beautiful Things: The Ferocious Ambition of The Swank Hotel (D.W. White Speaks with Lucy Corin)

CONVERSATION

A conversation between West Trade Review’s Fiction Editor D.W. White and the novelist and story writer Lucy Corin on her new book, The Swank Hotel, and the narrative, creative, and technical evolution of this remarkable novel.

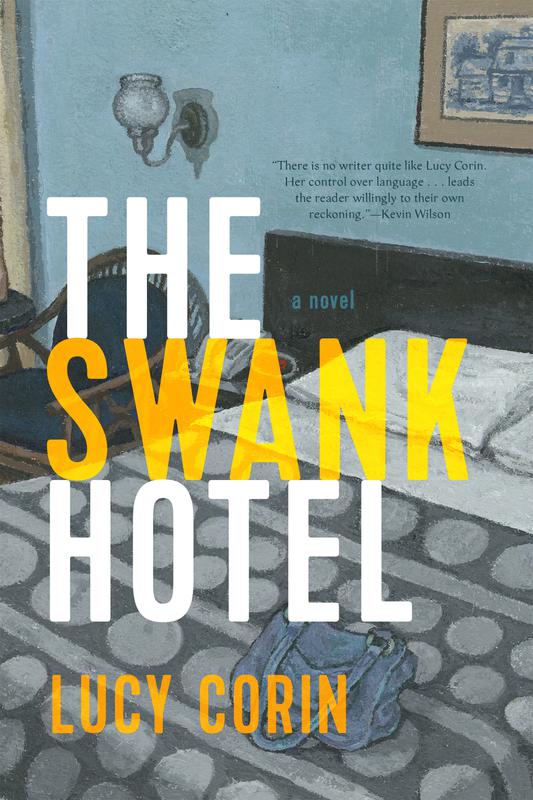

The Swank Hotel by Lucy Corin; Graywolf Press; 400 pages; $17

Lucy Corin is the author of the novel The Swank Hotel, as well as the story collections One Hundred Apocalypses and Other Apocalypses and The Entire Predicament, and the novel Everyday Psychokillers: A History for Girls. Her work has appeared in American Short Fiction, Conjunctions, Harper’s Magazine, Ploughshares, Bomb, Tin House Magazine, and the New American Stories anthology from Vintage Contemporaries. She is the recipient of an American Academy of Arts and Letters Rome Prize and a literature fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. She teaches at the University of California at Davis and lives in Berkeley.

D.W. White: One thing that I really thought was interesting about this book is how it intersects with this emerging trend in fiction right now to discuss the Great Recession, a literary movement that is fairly nascent. There’s Elizabeth Gonzalez James’ Mona at Sea, which came out earlier this year, and was great. And there’re others. But your book, of course, is set in the Great Recession and deals with it, but also it’s kind of a little bit of a cosmic background. I think it works really well as a temporal setting, but I think also this book and what it’s concerned about fundamentally could be set anytime in recent America. So what was the process, what was the decision-making behind that temporal location, and what did it allow you to do, setting the book when you did?

Lucy Corin: For me, writing a book is about feeling out the resonances between the thing that is occupying me overall and really particular individual daily experiences and wondering about where those resonances come from. In story writing, it’s pretty common to go into the psychological history of a character to try to connect those things. You find the thing in their background that helps explain the rest of the stuff the story’s about. Then there’s another way that says that we’re kind of symptoms of our surroundings. But in isolation, they both feel unsatisfactory, and a lot of writing this book was tracing those unsatisfactory explanations. The book starts with tracking these characters and what happens to them, but then I want to include in the book that hovering question around trauma, which is like, where does this come from? You feel like it comes from inside or it comes from outside, and what is that relationship, what does it feel like when the truth is both.

DW: That’s such a great answer. In terms of how we talk about stories, and then this will get us into craft, there is a distinction between internally-driven and externally-driven fiction. When I was reading this book, especially that first section — and this sounds cliché, but it’s not if one has read it — I was thinking of Infinite Jest, that type of metafictional, hysterical realism, a lot as I read The Swank Hotel. And with these wonderful interludes about the neighbors across the street and the lawsuit and everything, it’s that movement from a couple decades ago now. But as I was thinking about that, as I was going through the book, I realized there are a lot of books that have been written in the past twenty-odd years that try to mimic Infinite Jest or something. But this is not what that is.

LC: You know, I thought a lot about David Foster Wallace in the writing of this book, because, among other things, I wanted to be unapologetically expansive. But I thought of him especially when I had metafictional impulses. I say this with irony, but it’s how I was “raised” as a writer: that generation of white, male, post-modernists were core to my reading experience and the formation of my sensibility. Robert Cooper was an important teacher of mine. But I also always felt, in relation to that strand of American fiction, what I now understand as my feminist impulses and my queer reality, a suspicion of grandiosity and suspicion of authority that I think those texts and writers luxuriate in. Patterning, which is so beautifully heightened in DFW and related writers, is really important to me and I cherish it. But my sensibility comes from a really different place: how do you tell a story, especially about something that’s grand and big, when you don’t feel that your culture has endowed you with the authority to tell that story –– for good and bad reasons.

DW: One can see that in the techniques you use and things what you’re talking about, which brings another question. There’s so much of what I call risk-taking on the sentence level here, areas that ask a bit more of the reader, where they perhaps have to work a little bit. That is something that’s not being done to a large extent right now in fiction, this type of daring and innovation, and it’s one of the things I really love about this book.

LC: Core to me as fiction writer is that I both question convention and I love it and use it and exploit it and revel in it. Writing a book, or even a story, is always a long process of sorting through that piece’s relationship to convention. I don't advise that for anybody who wants to put out a lot of books. I feel like I'm very productive, but I have only written a couple of books out of all my productivity, because it's always a matter of sorting through which conventions I want to anchor the work in and which conventions to blow out the window, because I’m trying to show that there are ways of seeing things that are buried or that are not manifest yet, and that I want the book to manifest.

DW: That's a great argument for what's called experimentalism, right, which is not a great term, but in any event that's a great way of framing that concept.

LC: My family is filled with people who have both diagnosed and undiagnosed severe-to-mild forms of mental illness. So I grew up caring about it. I personally have not experienced extreme psychotic states. I've had my own traumatic experiences in my life that I think are on a continuum between perfect health and total incapacity. But I didn't write about mental illness in a direct way for a really long time. There was a period of time where in order to function in my life, I had to contend with it in a serious way. And really the only way that I contend with things as a human is through writing, and so when I started writing the book, it's not like I thought about it as my next masterpiece. I was just trying to function, you know what I mean? I was just trying to do what I do, which is to try and figure out the things of my life and in the world that I live in. And in some ways I do that the way everybody does that, by having friendships and relationships and therapists and that sort of thing. But the other way I do it is through art, through my art. And so, I don't think of art as therapy. But I think of making art as continuous with seriously addressing the things you care about most in your life and in the world. So that's what I did.

DW: One section that stands out with this in mind is the middle, which features a portion written by your sister. Was that a place where these concepts most notably interacted?

LC: So, it's a novel, and it's doing some weird things with form, and a lot of blurring between fact and fiction, and it's teasing, sometimes, about what the book is made of, what’s from my imaginative experience and what's from my lived experience. It was important to me to have that complexity in the book. I actually didn't say this directly before, but in my experience as a reader and as a person walking through the world, there's a lot out there that depicts mental illness that really upsets me and that I find painful, and that also made me not want to write about it at all for a really long time. So it was important to me to have the sense that I, the author, cared about this stuff in the real world built into the book in the way it was told. Because I'm not just a casual participant in this subject matter, right?

DW: There are many very serious and important and emotional elements that you address in The Swank Hotel. But one thing I'm interested in is the logistical-creative process in terms of crafting a book with this section, written as you say by someone else, that had to be fitted in. How did that come to be? Because it fits so well overall, tonally and otherwise.

LC: And it's pretty much right in the middle.

DW: Yes.

LC: I like that very much, formally.

DW: And it works. One could read this book and feel that it completely fits and doesn't feel like forced or off in any way. So how did that happen? Was that something that you came to via experimentation, trial-and-error? Obviously, you're exploring in this book, as you mentioned, these concepts in a way you hadn’t before, so there's a natural reason, from a craft perspective, why these two things would mesh together. But is that something you worked a bit to do it effectively, or how did that process unfold?

LC: It happened very late in the process. It happened during that period of time when you let an interested party read the book, and the interested party has feelings and thoughts and ideas. It happened then. And I had long talks with my sister and long talks with my editor. And that's where we landed with it. And what I can say about it is that I feel like I would be really proud of the book, that it was whole and complete, if that piece wasn't in it. But I also feel that the book is whole and complete and perfect with that piece. because it's so illustrative of, as I said before, that indeterminacy, that blurring, as it relates to the content of the book in that place.

DW: That's an incredible process and element to the work as a whole. What makes it so effective is how smoothly it's woven in the whole thing, into the tapestry of it.

LC: Okay, the swank hotel. My sister did the painting for the cover of the book, an image of a hotel room that is not swank. So for me that's the dynamic of that title. The desire for swank in a place that is not swank. It’s about when Ad says things like, “I could be magic, you know, where do you think Joan of Arc comes from? How do you think we get Joan of Arc? What do you think a shaman does, right?” That's the notion of glorious freaking possibility. The allure of madness is that things could be amazing. Things could be fantastic. And the tragedy is for most of us is that they're really not, they’re mundane, an awful kind of trudging. They’re those dust bunnies in the house that grow to the size of real bunnies, you know, they’re that stupid silverware that your parents picked up at thrift shops when you were a kid and that you're still eating with as an adult who has a “good job,” you know. So that's the contrast that I'm interested in, in the figure of the hotel.

DW: And the symbols for each chapter.

LC: They're just the symbols that go along the top row of your keyboard. I've been staring at those for ten years. It's just a little bit of the “this is written” thing. Also, the chapter titles are thematic. This chapter’s about money. That one, I want you to think about animals. I got a kick out of how the keyboard symbols seemed to match, or less directly, the chapter titles. Through a lot of the process of writing the book I’d make up symbols that showed, for me, the individual shape of each chapter, structurally, as I developed it. A knot, parallel lines, the shape of a phone cord, a starburst, stuff like that. For me, this was such a giant book, so organizing it was an absolute obsession through the process of writing. Organizing and reorganizing and just chart after chart after bulletin board, you know, psycho killer diagram with strings, thing after thing on the computer, off the computer, on the floor, everywhere. Just trying to keep track of it was a huge part of writing it. And so I was always looking for symmetries, and from the beginning I thought, “I'll write a book that is ten chapters long and has 200 pages, 20 pages in each chapter.” And I wanted it to be elegant and tidy that way in its broadest form, in part because I knew it was going to be so wild within it that I wanted something that really said “no, really, this book has a shape from the very beginning. Somebody authored this stuff and also our author is not a boundless mess.” So that TOC is, I think, the final effort at a chart that shows the shape of the book.

DW: I think you definitely succeeded in that goal.

There's a lot of humor here. Can you speak to the importance of humor in the book?

LC: Part of how I live is looking for the funny things. I'm a language first writer. And if you're interested in language, you best be interested in funniness, because that's such a large part of what language does, is be funny.

DW: And it's very true to life, too. Which is, of course, your focus as a writer, even things that are terrible. It's a human reaction to have this kind of dark comedy to it.

LC: Again, to go back to how I was raised. I knew I wanted to be an artist, but I didn't really know what sort of artist. When it was clear that I wanted to be a writer, it seemed to me that I shouldn’t do that because everybody knew that if you wanted to be powerful with your storytelling, you shouldn't be a writer. You should be working in film or TV, visual forms, whatever that's evolved into now. But it was clear to me that what mattered to me wasn't people looking at me and wondering what I thought about things; that was not why I was in the game. I was into storytelling for something else. I was into it because of my relationship with language.

DW: I’m interested in decision-making in fiction. In my opinion, reading the book, it felt like there was an effort to not stray too far from Em and her sister. Maybe stray far but not for too long, in that the book would go off in one direction or the other but always come back around to Em and Ad. We would learn about a character driving over the Great Smokey Mountains, and about this wild house being built, about the neighbor’s lawsuit. All manner of different things. But then it would come back around. Em is at her desk and she's trying to get this coat rack, trying to find Ad. So I'm curious about your decision making, how you balance those things.

LC: It was a project of the book to see exactly how far I could stray and still come back. It’s amazing to me, sometimes, how tight the expectations of most readers are when it comes to, “Why am I reading this?” It has to be really obvious that it all goes together and it all is related (and honestly, as a reader I am really pissed when I feel like I shouldn’t have had to read so much to get what I got) but I don’t think that directness is how significant learning takes place.

© 2021 West Trade Review

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Stay Connected to Our Literary Community. Subscribe to Our Newsletter

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

D.W. White is a graduate of the M.F.A. Creative Writing program at Otis College in Los Angeles and is at work on his first novel. He was a Fellow at Stony Brook University's BookEnds program for the 2020-2021 year. He serves as Fiction Editor for West Trade Review, has fiction published in Tulane Review and Trouvaille Review, and contributes reviews to the Chicago Review of Books and The Rupture. A Chicago ex-pat, he has lived in Long Beach, California, for seven years, where he frequents the beach to hide from writer’s block.