by Elisabeth Aiken

January 4, 2022

Elisabeth Aiken lives and teaches in central Florida. In addition to teaching American literature, her research interests include Appalachian and environmental literature as well as the intersections of ecocriticism and postcolonial studies. When she's not in class at Saint Leo University, she can be found reading or playing outside with her family.

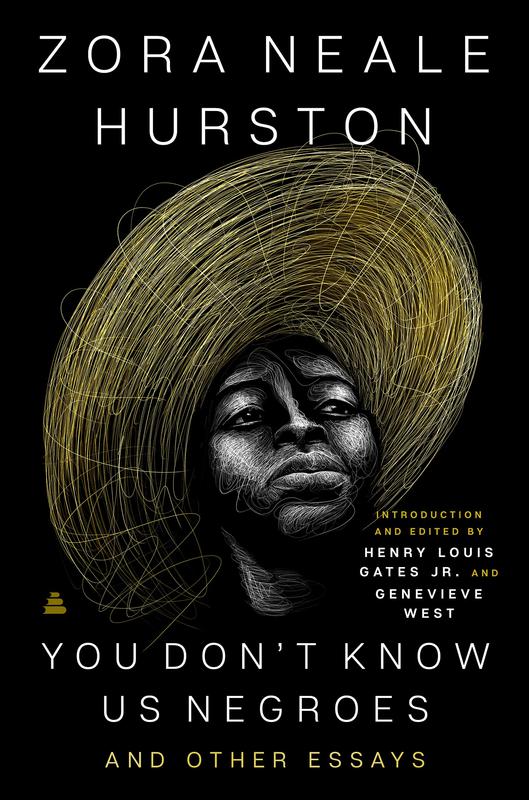

You Don't Know Us Negroes and Other Essays by Zora Neale Hurston; Amistad; 464 pages; $29.99

Zora Neale Hurston is a familiar figure often associated with the Harlem Renaissance, and her most known work of fiction, Their Eyes Are Watching God, is a frequently assigned text in many high schools across the country. Though Hurston may perhaps be best known today as a fiction writer, she was trained as an anthropologist at Howard University, Barnard College, and Columbia University, worked as a ethnographer and folklorist, and wrote and published dramatic pieces and nonfiction essays and articles, as well. You Don’t Know Us Negroes and Other Essays is an extensive collection of these nonfiction essays and articles that spans from the Harlem Renaissance to the early days of the civil rights movement. The collection of fifty essays is divided thematically into five sections (“On the Folk,” “On ‘Art and Such,’” “Race and Gender,” “On Politics,” and “On the Trial of Ruby McCollum”), though editors Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Genevieve West rightfully note that an essay’s appearance in one section does not negate its thematic relevance to another. Various essays are published in this collection for the first time, and others for the first time since their original publication—including the series of articles on the Ruby McCollum trial, which Hurston penned for the Pittsburgh Courier.

The text opens with an introduction by editors Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Genevieve West. Sweeping in scope, this primer to the collection highlights themes Hurston returns to time and again throughout the body of work, including art, linguistic expression, gender, and civil rights—all underpinned by a foundation in race. Gates, Jr. and West present Hurston’s writings as a kaleidoscope of these themes, which, when considered holistically, demonstrate Hurston’s desire to “lift the veil,” or, more explicitly, her “lifelong attempt to reclaim traditional Black folk culture from racist and classist degradations, to share with her readers the ‘race pride’ she felt, to build the race from within.”

In many of these essays, “building the race from within” means confronting the portrayals of African Americans. Throughout, Hurston’s use of allegory and metaphor is rife, but does not detract from her focused and pointed arguments. In the titular essay, “You Don’t Know Us Negroes” (ca. 1958), Hurston addresses the need for artistic portrayals of African Americans and presents readers with her scathing take on what she deems “Negro” literature. She argues that the portrayal of African Americans in literature, both since its inception and more specifically in the previous decade, failed to convey the richness of Black life, primarily to a white readership. She challenges the vaudeville and other fictional, “simple” portrayals of African Americans that are taken as true and thorough depictions of an entire people, tracing editors’ expectations of this portrayal back to Black writers who carefully control the image. Hurston writes, “You see, we have experienced the white man long enough to know that nothing pleases him more than to find out what he thought all along was the truth.” With pointed prose, Hurston challenges writers to “back their rubbish with something more substantial than the lay-figure of the past decade.”

Hurston’s voice rings clear from essay to essay, and in her quest to “reclaim traditional Black culture” she does not temper her criticism of various individuals or organizations. “Which Way, the NAACP?” is among the essays first published in this collection, and in this essay her discerning eye challenges the intentions and leadership of the NAACP. Gates, Jr. and West postulate this essay demonstrates her naïveté, as this essay is based upon assumptions that are incorrect (such as her claim that all schools in the south use the same curricula and textbooks). Erroneous assumptions notwithstanding, Hurston takes the NAACP (and W. E. B. DuBois himself) to task, questioning the organization’s wisdom of supporting forced school integration in the name of “advancement,” challenging what she saw as colorism within the organization, and ultimately proclaiming that NAACP leadership

. . . must take the realities into account if the organization expects to be of, for, and by the Negro people and cease to drive at what they feel Negroes ought to want or resent.

Where are you bound, NAACP?

The collection concludes with thirteen articles Hurston wrote on the trial of Ruby McCollum for the Pittsburgh Courier. In these articles, Hurston’s impressions steer her reporting of events—the first article is titled “Zora’s Revealing Story of Ruby’s 1st Day in Court!”—and her coverage indicates her support of McCollum’s case during her initial trial and following appeal, applauding McCollum as having “dared defy the proud tradition of the Old South openly and she awaits her fate with courage and dignity” after receiving a death sentence. In the final article, “My Impressions of the Trial,” Hurston draws upon her anthropological training to provide a study of both Judge Hal Adams and the African-American community of Live Oak, to which she remained an outsider. Hurston concludes that the events of the trial remain “behind a sort of curtain, on the other side of silence.”

You Don’t Know Us Negroes and Other Essays is an expansive and engaging collection that centers the challenging questions revealed when Hurston lifts the veil, as well as her smart and often-defiant responses. In every essay, Hurston’s unique voice swells with “race pride.” This collection chronicles an influential writer’s thoughts and reactions over the span of multiple decades, and Hurston scholars and casual readers alike will find it an illuminating compilation.

©2022 West Trade Review

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Lifting the Veil: Racial Pride and Zora Neale Hurston's You Don't Know Us Negroes and Other Essays

NONFICTION REVIEW

Stay Connected to Our Literary Community. Subscribe to Our Newsletter